Beth Anderson – Robert Ashley, Ear Magazine, an Opera, Graphic Scores, Electro-acoustic Excitement – Part 6 of her memoir

Comments Off on Beth Anderson – Robert Ashley, Ear Magazine, an Opera, Graphic Scores, Electro-acoustic Excitement – Part 6 of her memoirJanuary 22, 2020 by Admin

Read Part 1 of Beth’s memoir at http://www.soundwordsight.com/2019/07/beth-anderson-the-early-days-from-her-memoir/. Read Part 2 at http://www.soundwordsight.com/2019/08/beth-anderson-age-7-to-15-from-her-memoir/. Read Part 3 at http://www.soundwordsight.com/2019/08/beth-anderson-age-15-to-18-part-3-of-her-memoir/. Read Part 4 at http://www.soundwordsight.com/2019/09/beth-anderson-age-18-to-19-rorem-cage-swift-harrison-part-4-of-her-memoir/. Read Part 5 at http://www.soundwordsight.com/2019/10/beth-anderson-cage-riley-an-mfa-in-piano-part-5-of-her-memoir/’.

On March 3, 1973 my women composers group, Hysteresis, produced our first concert. I did my Peachy Keen-O for organ, electric guitar, vibraphone, some African drums from the dance department that Curt Sachs and I called membranophones, voices, audio tape, lights, and dance improvisation. It was a graphic score but I had a strong idea of what I wanted. I actually had to audition performers until I found people who could and would do what I wanted them to do. My mother said that it sounded like “haunted house music”. It was echoey and soft. The words were things like “supplication”, “What do you think of Elliott Carter?”, and “Who ya gonna yellow Faure?”. The audio tape portion had various sounds I had collected primarily in Kentucky including a talking mechanical Santa Claus and dinner conversation. Ana Perez, Kitty Mraw, Linda Collins and I played/spoke and I had four dancers from the dance department improvise. I asked the dancers to wear white and I used peach light. One of them was Molissa Fenley, the celebrated choreographer. Fifteen years later she told me that it was her first performance at Mills.

On March 3, 1973 my women composers group, Hysteresis, produced our first concert. I did my Peachy Keen-O for organ, electric guitar, vibraphone, some African drums from the dance department that Curt Sachs and I called membranophones, voices, audio tape, lights, and dance improvisation. It was a graphic score but I had a strong idea of what I wanted. I actually had to audition performers until I found people who could and would do what I wanted them to do. My mother said that it sounded like “haunted house music”. It was echoey and soft. The words were things like “supplication”, “What do you think of Elliott Carter?”, and “Who ya gonna yellow Faure?”. The audio tape portion had various sounds I had collected primarily in Kentucky including a talking mechanical Santa Claus and dinner conversation. Ana Perez, Kitty Mraw, Linda Collins and I played/spoke and I had four dancers from the dance department improvise. I asked the dancers to wear white and I used peach light. One of them was Molissa Fenley, the celebrated choreographer. Fifteen years later she told me that it was her first performance at Mills.

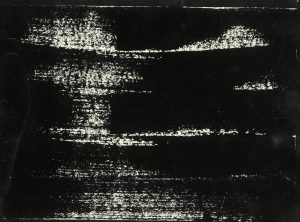

At right is the graphic score of Peachy Keen-O.

At right is the graphic score of Peachy Keen-O.

Hysteresis was an interesting group but when we had meetings we all sat around and talked and talked. In the spirit of early 1970’s feminism, we did not allow ourselves a leader, so there were no rules. There was no order or logic as to how we decided what we wanted to do. Eventually we would come to a consensus. I had never been good in groups and the meetings gave me stomach aches. The men around us called it Hysterical and Hysterectomy. I thought of it as a means to transform history, to create change by exerting group force, and in particular, to give women composers a hearing. Music by women was rarely performed on the regular Saturday afternoon new music concerts. Our first Saturday concert was a very good day for me, as it turned out.

After the show, the head of the upstairs music department, also known as the Center For Contemporary Music, sent a student to bring me to him. I hadn’t realized Robert Ashley was in town. He was often in New York with Mimi Johnson since he was separating from Mary Ashley, the video artist. I knew who he was and had heard students talk about him but I had never spoken to him. I was a downstairs music grad student and he was the head of the desirable upstairs musical universe. The CCM had an electronic music and recording studio, all the tape recorders, synthesizers, and electronics, and a curriculum I craved.

Try as I might, I had not had a reason to stop practicing the Chopin g-minor Ballade for Bernard Abramovitch my first year at Mills, or the Stravinsky Sonata for Naomi Sparrow my second year until that moment when Ashley sent for me. It was almost two years of anticipation. I was ready to do my MFA recital in April. If I didn’t find a way to be a composer soon, I was going to have to go home to Kentucky and teach piano and work at the post office. That was a fate that I considered in the direction of death.

Robert Ashley

I climbed the stairs and there he was at the coffee machine. Ashley was a handsome forty-two. He was wearing his dressed down wardrobe of cowboy boots, jeans and a button-down shirt. Bob had the most beautiful hair. I can’t remember if it was grey or white in 1973 but it was full, a little over the collar, and nicely cut. He had an eye for presentation.

He shook my hand and told me he liked my piece. He sat on a metal folding chair and I sat across from him on the beat-up couch in the hangout area outside the office. He asked me if I was interested in doing an MA in Composition next year and I said yes. I said yes but I told him there was a money issue and I was worried about the language requirement. Despite years of French in high school and college I doubted I could pass a serious timed reading test. He said not to worry about it. He would find me some grant money and I could have a work-study job. He also said he would help me with the French. He told me that if I wanted to be a composer, I could be. In my mind fireworks were exploding. It was as though he had told me, “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus.”

I do not think that Ashley was ever again as interested in my music as he was that day. But it didn’t matter. He had done the most important thing for me that anyone could have done at that moment in my life. He had given me praise and permission to do what I wanted to do in the first place. And he had made it possible for me to acquire a degree in composition to kosher my decision and, I hoped, my music.

Robert Ashley at the ONCE Festival

That was the beginning. Ashley had been a part of the legendary ONCE Festival and the Sonic Union, a collective of illustrious experimental musicians (1966-76), before coming to Mills. He loved to collaborate with composers, video artists, performers and technical wizards of sound and light. He was a popular guy and people enjoyed being with him and helping him create his pieces.

As my teacher, he left everything to be desired. The year I spent on my degree in composition, he was my primary teacher and the head of my degree committee. Yet he spent almost the whole school year in New York with his new love. He lived in New York so completely that he established residency and was given a New York State Arts Council Grant.

The two classes I remember having with him were spent sitting on the stage of the theatre with perhaps six other students. Bob still smoked then and he rolled his own. Someone asked him why and he said because it gave him something to do while he was thinking of what he was going to say. We did not analyse scores or listen to recordings. Bob talked and rolled and smoked, and we listened and watched. He spoke softly and there was a lot of silence around his ideas. Bob liked for us to watch him do things slowly. He believed in process which was high status in the art world. Collage was a slow second. A variety of composers created music that was considered process music including Carter, Stockhausen, Cage and Reich. Ashley said that all of my music was collage. After that piece of news and despite my being able to describe the processes by which my works were derived, he wasn’t there. There was white noise where our teacher-student relationship should have been. As a mentor, he was sensory deprivation itself.

Bob also taught us (Peg Ahrens, Paul DeMarinis, Paul Robinson, Marc Grafe, John Bischoff) that when going to meet grant agency personnel, always take a cab. He said not to walk and sweat because the sweating would be interpreted as having something to hide and then the funding would not be granted. Since Bob had gotten the Rockefellar funding for the CCM at Mills, we figured he knew.

Ashley played a pivotal role in my life and nothing more, or so it seemed. He was like the hole in a bagel–a positive negative. He gave me the space to write the music I wanted to write without any information, guidance, advice, recommendation, support, or interference. On the other hand, he got me the job in the dance department and he invited me to run a women composers’ festival. From these two incredibly helpful moves, I made a living for twenty years working for dancers and ran several other women composers’ classes, festivals, and concert series.

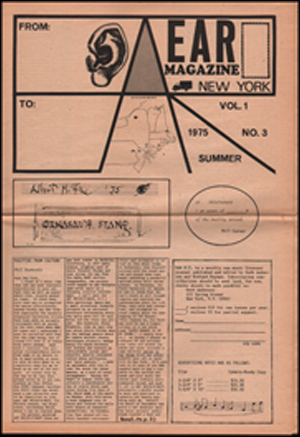

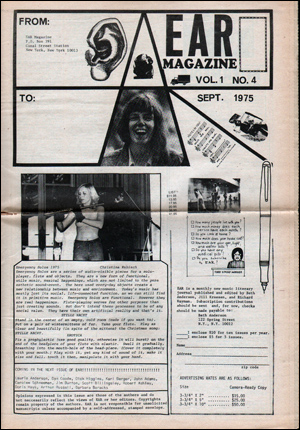

Ear Magazine

On top of everything else that was started in motion 3/3/73, Anne Kisch, who had started Ear Magazine with Charles Shere in January 1973, asked to publish the score of “Peachy Keen-O” in Ear in the fifth issue (May). When I didn’t hear from her in April, I called Charles and he told me that she had moved to France and that he needed someone to help him publish Ear. I took the “job” and published my score myself in the fifth issue. Charles was traveling a lot then and he brought over the blue lined layout forms and told me what to do and then he left town. I was in shock but I typed the copy on my IBM typewriter and laid it out on my bed. The day it was going to be printed, Charles appeared and corrected my multitudinous misspellings with his rapidograph pen and that’s the way it went out. Charles and I put out this magazine about eleven times a year. When I moved to New York in February 1975, we did a February issue in California (Vol.3 #2) and I did a March issue in New York (Ear New York Vol. 1, #1). The California Ear continued for a number of years and the Ear New York continued until about 1991, giving the country stereophonic scores/reviews/interviews/ideas. Nam June Paik said that the NY Ear should be called the NY Eye & Ear (after the infirmary) but visual art was not my focus and we didn’t have the money to reproduce images especially well. Charles had a Fluxus (an art movement that championed absurdity, freedom, and fun that was perhaps related to the Dada movement) orientation that I enjoyed but when I came to NY and acquired new partners in the layout process (Jill Kroesen, Alison Knowles, and quite a number of other talented people), the columns became more orderly. I was told that New Yorkers did not have the leisure to follow print that changed its orientation and articles that were continued on eight different pages. The confusion and messiness/artfulness were part of the charm of the California Ear. The effort to be a “real magazine” with vodka ads, many pages, neat text and big budgets killed the New York Ear. I had published the low budget version and broken even—given the kindness of subscribers and a few community advertisers. I never made a thing in the seven years I did Ear but I didn’t go out of business.

On top of everything else that was started in motion 3/3/73, Anne Kisch, who had started Ear Magazine with Charles Shere in January 1973, asked to publish the score of “Peachy Keen-O” in Ear in the fifth issue (May). When I didn’t hear from her in April, I called Charles and he told me that she had moved to France and that he needed someone to help him publish Ear. I took the “job” and published my score myself in the fifth issue. Charles was traveling a lot then and he brought over the blue lined layout forms and told me what to do and then he left town. I was in shock but I typed the copy on my IBM typewriter and laid it out on my bed. The day it was going to be printed, Charles appeared and corrected my multitudinous misspellings with his rapidograph pen and that’s the way it went out. Charles and I put out this magazine about eleven times a year. When I moved to New York in February 1975, we did a February issue in California (Vol.3 #2) and I did a March issue in New York (Ear New York Vol. 1, #1). The California Ear continued for a number of years and the Ear New York continued until about 1991, giving the country stereophonic scores/reviews/interviews/ideas. Nam June Paik said that the NY Ear should be called the NY Eye & Ear (after the infirmary) but visual art was not my focus and we didn’t have the money to reproduce images especially well. Charles had a Fluxus (an art movement that championed absurdity, freedom, and fun that was perhaps related to the Dada movement) orientation that I enjoyed but when I came to NY and acquired new partners in the layout process (Jill Kroesen, Alison Knowles, and quite a number of other talented people), the columns became more orderly. I was told that New Yorkers did not have the leisure to follow print that changed its orientation and articles that were continued on eight different pages. The confusion and messiness/artfulness were part of the charm of the California Ear. The effort to be a “real magazine” with vodka ads, many pages, neat text and big budgets killed the New York Ear. I had published the low budget version and broken even—given the kindness of subscribers and a few community advertisers. I never made a thing in the seven years I did Ear but I didn’t go out of business.

Dick Higgins, the writer/publisher of Something Else Press and Alison Knowles’ ex-husband, told me that I should shut down and sell runs of back issues to make some money but I wanted it to go on. I gave it to Charlie Morrow and his New Wilderness Foundation. I really enjoyed doing Ear. I loved being in touch with so many composers and artists. The problem was that Ear dealt with an aesthetic that I had begun to reject. By 1979, I couldn’t keep writing the kind of music I had begun to write and do Ear. Dick was probably right. I thought Charlie could keep it going indefinitely. Perhaps it was a change in aesthetics that ended Ear rather than simply getting too big for its budget. By the late 1980’s music was going in a lot of directions besides those Cage, Glass, and Carter had proposed. There was cross-over rock influence and jazz influence and what the composer, Michael Sahl called my “looney tunes and merry melodies”.

Dick Higgins, the writer/publisher of Something Else Press and Alison Knowles’ ex-husband, told me that I should shut down and sell runs of back issues to make some money but I wanted it to go on. I gave it to Charlie Morrow and his New Wilderness Foundation. I really enjoyed doing Ear. I loved being in touch with so many composers and artists. The problem was that Ear dealt with an aesthetic that I had begun to reject. By 1979, I couldn’t keep writing the kind of music I had begun to write and do Ear. Dick was probably right. I thought Charlie could keep it going indefinitely. Perhaps it was a change in aesthetics that ended Ear rather than simply getting too big for its budget. By the late 1980’s music was going in a lot of directions besides those Cage, Glass, and Carter had proposed. There was cross-over rock influence and jazz influence and what the composer, Michael Sahl called my “looney tunes and merry melodies”.

Composing at Mills

To return to life at Mills, studying with Bob Ashley left us all with a lot of free time. I wrote music. In 1973 I wrote an opera , “Queen Christina”, a series of electro-acoustic pieces using graphic scores including “Tulip Clause”, “Valid For Life”, “Music For Charlemagne Palestine”, “I Am Uh Am I”, “Peachy Keen-O”, “Tower Of Power”, “Recital Piece”, “Music For Myself”, and “Hallophone”. I also made two audio tape pieces, “Thus Spake Johnston” using Jill Johnston’s voice and “Tulip Clause and BuchlaBird Hiss Down The Road Of Life”, and my first text-sound composition, “Torero Piece”. Some of these were commissions and all of them were performed.

To return to life at Mills, studying with Bob Ashley left us all with a lot of free time. I wrote music. In 1973 I wrote an opera , “Queen Christina”, a series of electro-acoustic pieces using graphic scores including “Tulip Clause”, “Valid For Life”, “Music For Charlemagne Palestine”, “I Am Uh Am I”, “Peachy Keen-O”, “Tower Of Power”, “Recital Piece”, “Music For Myself”, and “Hallophone”. I also made two audio tape pieces, “Thus Spake Johnston” using Jill Johnston’s voice and “Tulip Clause and BuchlaBird Hiss Down The Road Of Life”, and my first text-sound composition, “Torero Piece”. Some of these were commissions and all of them were performed.

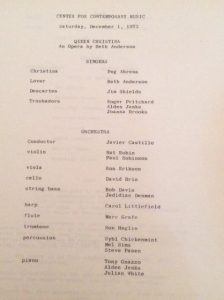

My three character opera, “Queen Christina”, dealt with the queen of Sweden’s life from birth to her abdication in 1654. Queen Christina lived 1626-1689 and was considered the most intelligent ruler of her time. I read about her in a very small book about famous women who were meant to be feminist heroines. The three characters in my opera were Christina, Ebba her lady in waiting and lover, and Rene Descartes who spent time in Sweden at Christina’s invitation. This opera, performed at Mills on December 1, 1973, was an enormous collage and a community effort, as well. I sent letters to local gay and lesbian organizations requesting their participation in the crowd scenes and they came. I gave some people spears to serve as guards of the queen and everybody else got glittery crowns. Tony Gnazzo contributed his many many slides of the painting, The Blue Boy by Thomas Gainsborough, and as the orchestra played my Tulip Clause, Tony’s amplified voice intoned, “Queen Christina at birth.” Then he showed another slide of The Blue Boy and said, “Queen Christina at age one.” This went on for about ten minutes until she was nineteen. This was the year that Descartes came to Sweden to be with her as her teacher and friend, or that’s what I had read. He was the one who said that she was the most intelligent ruler of her time. Much later I discovered that they actually did not get along well and that he died there of pneumonia, or he was assassinated, which is a much better, but unsubstantiated story.

The baritone role of Descartes was sung by Jim Shields who was in the San Francisco Opera Chorus at the time and a grad student at Mills. Christina was sung by the soprano-composer, Peggy Ahrens. Since I could not find anyone to sing Ebba’s mezzo part, I did it myself. For the coronation scene most of the audience was on stage along with the cast and the composer-saxophonist, Peter Gordon showed a film of drag show contestants being crowned queen simultaneously. After the coronation, Christina took her throne and a group of dancers from the dance department did a modern improvisation to the pre-recorded taped “Peachy Keen-O”. There was also a ballet section to fete the queen. The songs were accompanied by the small orchestra, but since some instruments were in short supply, the accordion filled out the inner parts, which gave the music a French café feel. Composer-guitarist, Bob Davis played string bass and he was twenty minutes late. We held the curtain for him. He came in drag and had trouble with his dress and wig. Since he had the bass part, we couldn’t start without him. After twenty minutes, Robert Commanday from the San Francisco Chronicle left saying that he did not wait twenty minutes for anything. Charles Shere, a composer as well as music critic for the Oakland Tribune wrote a descriptive review.

The baritone role of Descartes was sung by Jim Shields who was in the San Francisco Opera Chorus at the time and a grad student at Mills. Christina was sung by the soprano-composer, Peggy Ahrens. Since I could not find anyone to sing Ebba’s mezzo part, I did it myself. For the coronation scene most of the audience was on stage along with the cast and the composer-saxophonist, Peter Gordon showed a film of drag show contestants being crowned queen simultaneously. After the coronation, Christina took her throne and a group of dancers from the dance department did a modern improvisation to the pre-recorded taped “Peachy Keen-O”. There was also a ballet section to fete the queen. The songs were accompanied by the small orchestra, but since some instruments were in short supply, the accordion filled out the inner parts, which gave the music a French café feel. Composer-guitarist, Bob Davis played string bass and he was twenty minutes late. We held the curtain for him. He came in drag and had trouble with his dress and wig. Since he had the bass part, we couldn’t start without him. After twenty minutes, Robert Commanday from the San Francisco Chronicle left saying that he did not wait twenty minutes for anything. Charles Shere, a composer as well as music critic for the Oakland Tribune wrote a descriptive review.

Getting this opera on stage was an experience. There were so many moving parts and no money at all. Without the generosity of all the performers and the conductor, Javier Castillo, and the participation of local composers and groups, I could not have managed it. It was exhausting, but a lot of fun.

Graphic scores did not use traditional music notation. They used a variety of symbols often including wiggly lines, triangles and arrows to indicate pitch change. Composers had begun creating them in the 1950’s and they had become less and less like tradiitonal notes on staves over time. Mine were ink drawings that sometimes included words or numbers and used either pen or brush or Letraset rubdown letters.

In any case the music I made in 1973 included the graphic score, “Music For Charlemagne Palestine”. Bob Ashley invited Charlemagne to Mills to do a concert of his music that was strikingly beautiful and soft. I connected the sound image of his billowing overtones with rabbits and made this piece in his honor. Later on I met him again in New York and he was wearing a long rabbit coat.

The basic idea for the use of this score was to play it softly, improvisationally, and continuously. It had 3 movements. The one that looked like a rabbit was the 1st and 3rd movement (a kind of Da Capo). The one that looked a little like a lettuce patch was the 2nd movement. I hoped that the second time the rabbit part was played, it would be somewhat different. Every time any score was performed it was slightly different, but with graphic scores, it was even less likely to match any other performance. This one was performed for organ solo, for string quartet, and once, for string quartet with organ. As far as I know, it was not performed after 1976. One of those rare performances was by the Ear Ensemble at the Intersection Coffee House in San Francisco.

For more information about graphic scores the original source was John Cage and Alison Knowles’, Notations. New York: Something Else Press, 1969. For a more recent source in which I also appear, see Theresa Sauer, Notations 21, Mark Batty Publisher, 2008. The Sauer book shows my score for “Tower Of Power” for organ and quad tape (the score for which is at left). That piece was commissioned by Linda Collins for a performance in the Mills Chapel March 4, 1973, the day after the fateful premiere of “Peachy Keen-O”.

For more information about graphic scores the original source was John Cage and Alison Knowles’, Notations. New York: Something Else Press, 1969. For a more recent source in which I also appear, see Theresa Sauer, Notations 21, Mark Batty Publisher, 2008. The Sauer book shows my score for “Tower Of Power” for organ and quad tape (the score for which is at left). That piece was commissioned by Linda Collins for a performance in the Mills Chapel March 4, 1973, the day after the fateful premiere of “Peachy Keen-O”.

The instructions for “Tower Of Power” were to hold down as many keys and pedals as possible using only the performer’s body, at as loud an amplitude as possible, using both the performer’s ears and equipment to decide how loud to be, and to do it for a minimum of 5 minutes, using yourself and your audience to decide how long to continue. During the performance the timbre was to be changed a minimum of five times, without letting any notes up and avoiding any sharp contrasts. The exact organ used for the performance dictated the possibilities for the timbral changes. Four rehearsals of the piece were to be recorded and played back in exact synchronization with the performance through four speakers placed symmetrically around the church or concert hall, taking into consideration the origination of the organ sound. They were all required to blend. The duration of the piece was to be in multiples of five minutes…5 minutes or 10 minutes or 15 minutes, and so on, as the performer chose. All the rehearsals needed to be the same length as the performance. The performer was to “prepare your spirit mind ears body family, but avoid any discussion of the sound.”

The score was made by making a five line staff with a wide brush. The brush filled in the staff with sound. The score was originally about 3 feet wide by 4 feet long. It looked like a large painting sitting on the music rack of the organ.

The first performance was taped and many years later Pogus included that original Linda Collins performance on the CD they did of my work in 2003. Roger Johnson’s Schirmer book, Scores, from 1978 anthologized this piece as well as my “Valid For Life”, another graphic score.

The first performance was taped and many years later Pogus included that original Linda Collins performance on the CD they did of my work in 2003. Roger Johnson’s Schirmer book, Scores, from 1978 anthologized this piece as well as my “Valid For Life”, another graphic score.

Another score with a graphic element, “Tulip Clause”, came into existence as a commission from the San Francisco Conservatory New Music Ensemble. Their composer-conductor, John Adams, arranged this. This commission was a thrill. First of all I admired John Adams tremendously. He was a wonderful conductor. He was very energetic and he made interesting programs including Edgard Varese’s “Ionization”, music by Ives and Cage and newly commissioned music. Secondly there was an actual fee for the music. That was a first for me. And the performance was at the San Francisco Museum of Art, a glorious venue.

He offered me a long list of instruments I could use including electronics and voice. I chose the instrumentation based on numerology. By this point I had read a book on the subject and understood that the odd numbers were considered masculine and the even numbers were feminine. So if cello, coded into numbers, came out even, then I could have a cello in my piece. This method of choosing was a combination of Cage’s chance operations and my feminism.

Here is one possible coding system. You can see that A is 1 and H is 8, for example.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

a b c d e f g h i

j k l m n o p q r

s t u v w x y z

Using that code, you get: cello=3+5+3+3+6=20 and 2+0=2 (a feminine choice) or, flute=6+3+3+2+5=19 and 1+9=10 and 1+0=1 (a masculine choice) and then of course after I got the instruments I could use, I decoded a text of some sort using some code or group of modulating codes. In this case I used part of the text of a lecture given at the Chabot Observatory regarding Jupiter and the tape was also made from that speech. This observatory was on Skyline Boulevard in Oakland.

The end result was that the piece used tenor voice, alto flute, B-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, tenor sax, string bass, cello, organ, timpani, and electronic tape. It had numerologically derived pitches that were arranged in a graphic score made from the rubdown letters. The title came from a dreamt layout for the performers on stage in the shape of a tulip. How this spacial tulip related to the United States’ space program’s scientific exploration of Jupiter is a bit obtuse so many years later.

I did have a female cat that was a gift from bay area clarinetist Tom Rose, that I named Jupiter, at this time. Tom’s children were tormenting the cat and she would not agree to come out from under their couch, so he brought her to me. I named her Jupiter because I wanted her to grow up to be a large cat but she did not exceed eight pounds during her long life.

I did have a female cat that was a gift from bay area clarinetist Tom Rose, that I named Jupiter, at this time. Tom’s children were tormenting the cat and she would not agree to come out from under their couch, so he brought her to me. I named her Jupiter because I wanted her to grow up to be a large cat but she did not exceed eight pounds during her long life.

After the music’s premiere in San Francisco with Tom Buckner, baritone,”Tulip Clause” was performed at the Cabrillo Festival in Aptos, California on August 23, 1974 with Paul Sperry, tenor. Later the scores of “Tulip Clause” and “Torero Piece” appeared in a book entitled Ed Vogelsang-Views Beside… edited by Fritz Balthaus, published in Berlin in 1982.

Category Sight, Sound, Word | Tags:

Comments Off on Beth Anderson – Robert Ashley, Ear Magazine, an Opera, Graphic Scores, Electro-acoustic Excitement – Part 6 of her memoir

Sorry, comments are closed.