New Marc Blitzstein CD and 2 New Books on Leonard Bernstein

1July 10, 2018 by Admin

New Marc Blitzstein CD and 2 New Books on Leonard Bernstein

© 2018 by Leonard J. Lehrman

Blitzstein’s New/Old Cradle Will Rock

Conductor John Mauceri has done it again, in productions and then recordings, bringing new light to Bernstein and Blitzstein masterpieces that had hitherto not enjoyed the full appreciation they deserve. First there were the Scottish Opera versions in 1988 of Bernstein’s Candide and in 1991 of Blitzstein’s Regina, both restoring and exploring sketches and other materials that had been cut, some of them for good reason, but giving future producers the opportunity to choose among them. Now he has conducted, and Bridge Records has released, the original version, with full orchestra, of the work that launched Bernstein’s career at Harvard as conductor, pianist and producer of socially conscious musical theater, Blitzstein’s Brechtian play in music, written “at white heat” in 5 weeks, in 1936: The Cradle Will Rock.

Conductor John Mauceri has done it again, in productions and then recordings, bringing new light to Bernstein and Blitzstein masterpieces that had hitherto not enjoyed the full appreciation they deserve. First there were the Scottish Opera versions in 1988 of Bernstein’s Candide and in 1991 of Blitzstein’s Regina, both restoring and exploring sketches and other materials that had been cut, some of them for good reason, but giving future producers the opportunity to choose among them. Now he has conducted, and Bridge Records has released, the original version, with full orchestra, of the work that launched Bernstein’s career at Harvard as conductor, pianist and producer of socially conscious musical theater, Blitzstein’s Brechtian play in music, written “at white heat” in 5 weeks, in 1936: The Cradle Will Rock.

As I wrote in my New Music Connoisseur review of the June 2017 Opera Saratoga production recorded here (posted at http://ljlehrman.artists-in-residence.com/PoliticalMusicalTheatre.html), hearing the original orchestration for the first time since the miscast NY City Opera production of 1960 is an ear-opener. Elie Siegmeister had admired the use of Hawaiian guitar in particular, and the overall effect puts the sound ambience much closer to that of Kurt Weill than the other predominant influence: Hanns Eisler. (Blitzstein’s 1934 Children’s Cantata, “Workers’ Kids of the World, Unite,” dedicated to Eisler, is slated to receive its world premiere in NJ & NY next January. An excerpt has just been posted on YouTube here: https://youtu.be/2zXV50lucbM.

The excellent opera singers Ginger Costa-Jackson, Matt Boehler and Chrisopher Burchett headed the cast as the Moll, Mister Mister and Larry Foreman. Most of the small errors heard onstage were corrected by the time the (live) recording was made June 13-16, 2017, the single (repeated) exception being Editor Daily’s characterizing Honolulu as “that far” instead of “that fair” land. The sound is all clearly miked, the diction a bit drawn out, and the underlying bass drum in the Drugstore Scene comes across as a little more oppressive than it was in the house, but overall the text comes across well. The album notes include bios of six of the leads, but none for the ensemble singers, all members of the company’s Young Artist Program. At least one of those, Nina Spinner, who comes close to stealing the show as Ella Hammer, deserves more.

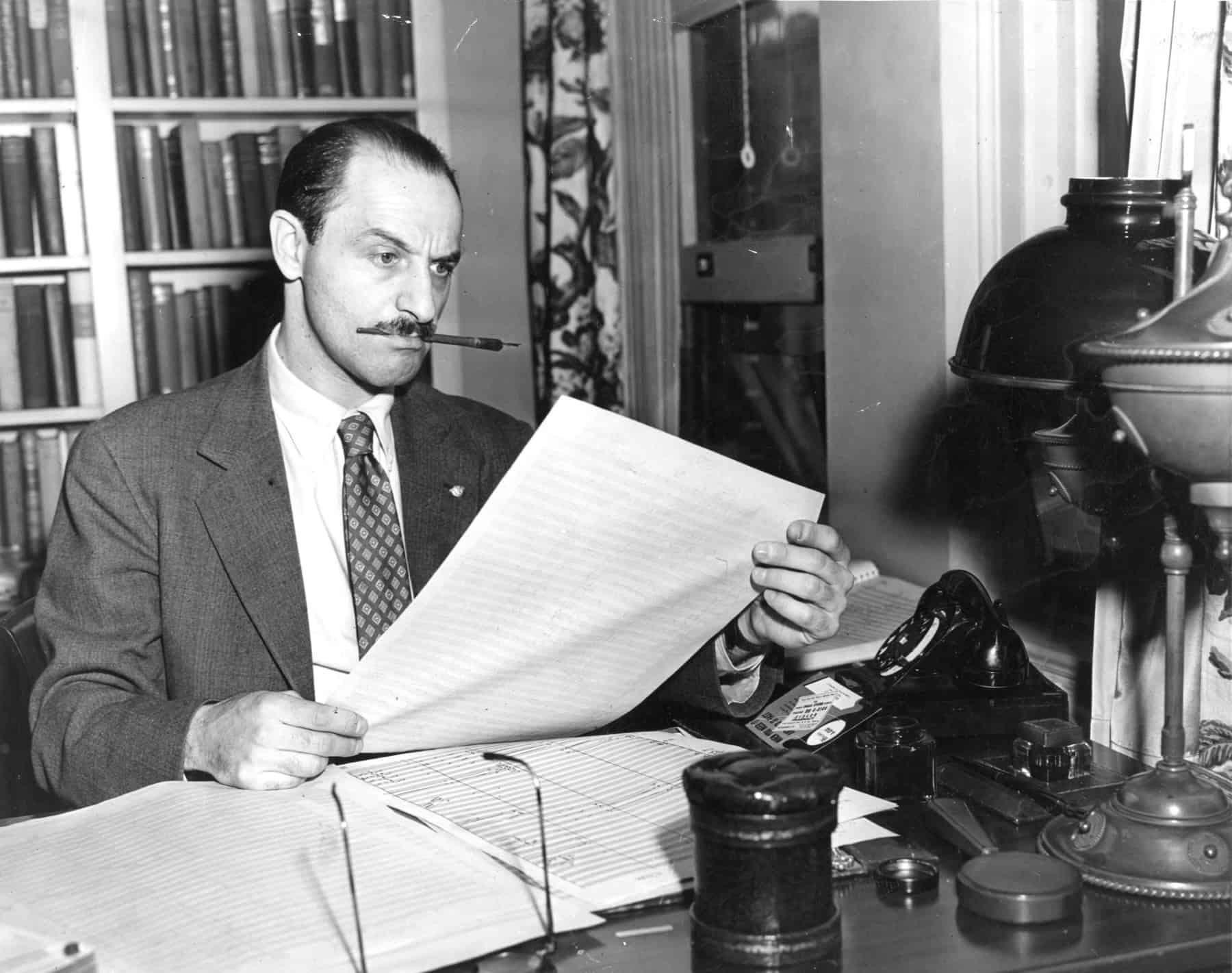

The album includes a bonus “Appendix” in which Marc Blitzstein tells in his own words the story of the creation and opening of Cradle in 1936-37. This recording of his voice, which first appeared in 1956 on an LP published by Westminster Spoken Arts (uncredited here), is so spine-tingling, I get chills every time I have listened to it, or played it for nearly all the casts of the Blitzstein works I’ve produced over the years (including Cradle, I’ve Got the Tune, Harpies, Tales of Malamud, and Sacco and Vanzetti, plus excerpts from No for an Answer, Goloopchik, The Airborne Symphony, and Juno).

The album includes a bonus “Appendix” in which Marc Blitzstein tells in his own words the story of the creation and opening of Cradle in 1936-37. This recording of his voice, which first appeared in 1956 on an LP published by Westminster Spoken Arts (uncredited here), is so spine-tingling, I get chills every time I have listened to it, or played it for nearly all the casts of the Blitzstein works I’ve produced over the years (including Cradle, I’ve Got the Tune, Harpies, Tales of Malamud, and Sacco and Vanzetti, plus excerpts from No for an Answer, Goloopchik, The Airborne Symphony, and Juno).

The album also includes liner notes by Howard Pollack (whose name is misspelled Pollock). Despite his erroneous listing here of Bernstein’s Boston premiere of the work as 1937 (it was 1939), Pollack’s insights are often invaluable, as noted in my review of his Blitzstein biography, posted here: http://ljlehrman.artists-in-residence.com/articles/OutlookPollackMBrev.html. He has recently published a brilliant biography of the writer John LaTouche, which I’m still reading and plan to review.

Mauceri’s own notes are also stunning. Regarding the aforementioned NY City Opera production of 1960: “…some New York critics thought the parable to be old fashioned since the issues of a rich man and his family taking over and corrupting every aspect of society were things of the past.” (Ha!)

“Without a single updated text change, and maintaining the story in the late 1930s, …this tale of nepotism, bribery, violence, prostitution on every level, fear of change, the manipulation of news, the suspicion of immigrants, and the buying and selling of the middle-class, were not things of the past. All we had to do was perform it as it was written.” (His full essay is posted at https://lithub.com/bringing-the-cradle-will-rock-back-to-life/.)

Well, almost. Actually, a couple of small changes made in 1960 by Blitzstein himself were kept for 2018. A reference to Carole Lombard was changed to Greta Garbo (notwithstanding the original’s purer rhyme with “never get tir’d” in “Croon Spoon”). And perhaps most interestingly, the opening of the second verse of Ella Hammer’s song, originally “Joe Worker just drops. Right at his working he drops” became “Joe Worker was pushed. He never fell, he was pushed.” What was Blitzstein thinking when he changed that line? I can tell you exactly what: In Act I Scene 2 of Sacco and Vanzetti, the work he had just begun, commissioned by the Ford Foundation and optioned by the Met, Vanzetti’s First Aria details the death of their anarchist comrade Andrea Salsedo, who fell out of a window on the 14th floor, but for whose death the police claimed not to have been responsible. “I know it for a lie,” Vanzetti cries out, warning: “I fear that we are next.” As I have written elsewhere, and urged Mauceri personally, his next project should be the long-awaited orchestral premiere of this work, which Blitzstein himself called his magnum opus.

Please see http://ljlehrman.artists-in-residence.com/SaccoAndVanzetti.html.

Bernstein by His Valet (and Editor)

Charlie (not Charles, Charlie) Harmon’s new book, On the Road & Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein : My Years with the Exasperating Genius, published by Charlesbridge in Watertown, Mass., is, as Harold Prince writes in his Foreword, “among the first” written in celebration of Bernstein’s centenary, being celebrated Aug. 25, 2017-Aug. 25, 2019. (See our contributions to those celebrations at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLmhHI8m9j-XuPZ-lBCy4YTqgwxoReZAl- and https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLvJ1IwK-e7t_CDNakodjQxb_YQS_J1JRR.) It reminds me a bit of James E. Amos’s contemporaneous “Theodore Roosevelt: A Hero to His Valet,” whom we’ll no doubt be hearing a lot more of next year, the centennial of TR’s death. (The centenary of the birth of his grandson, J. Willard Roosevelt, was celebrated this past April 20, 21 & 22; see, respectively, https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLmhHI8m9j-XuCsz4PwBYfngvKPNOoOLv0, https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLmhHI8m9j-Xt3T9fjZueGpR4D2_VrRFp5 and https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLmhHI8m9j-Xsv9druVwPWmIoHedZWQWVT).

Charlie (not Charles, Charlie) Harmon’s new book, On the Road & Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein : My Years with the Exasperating Genius, published by Charlesbridge in Watertown, Mass., is, as Harold Prince writes in his Foreword, “among the first” written in celebration of Bernstein’s centenary, being celebrated Aug. 25, 2017-Aug. 25, 2019. (See our contributions to those celebrations at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLmhHI8m9j-XuPZ-lBCy4YTqgwxoReZAl- and https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLvJ1IwK-e7t_CDNakodjQxb_YQS_J1JRR.) It reminds me a bit of James E. Amos’s contemporaneous “Theodore Roosevelt: A Hero to His Valet,” whom we’ll no doubt be hearing a lot more of next year, the centennial of TR’s death. (The centenary of the birth of his grandson, J. Willard Roosevelt, was celebrated this past April 20, 21 & 22; see, respectively, https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLmhHI8m9j-XuCsz4PwBYfngvKPNOoOLv0, https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLmhHI8m9j-Xt3T9fjZueGpR4D2_VrRFp5 and https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLmhHI8m9j-Xsv9druVwPWmIoHedZWQWVT).

Charlie’s story is a compelling one of tension, exhilaration, frustration, and to at least some extent satisfaction, one in which I myself played a small, peripheral role. When the Metropolitan Opera hired me as Assistant Chorus Master in 1977, at least partly on Bernstein’s recommendation, I left academia and found I couldn’t go back, being deemed “overqualified” for any positions open. Before leaving for Europe in 1979, where I would work in German-speaking theaters for 7 years, I asked Bernstein’s manager, Harry Kraut, if there was any way I could work for him. “The only job opening we have,” he told me, “is for a valet.” That was the job Charlie Harmon, a Carnegie-Mellon BFA trained musician and editor at Tams-Witmark, walked into in 1981, after several “assistants” had come and gone, “like the change of seasons in New York.” Only Charlie remained for four years, and left not for a job elsewhere, despite many vicissitudes and a frequent gnawing feeling of being “discarded,” but having become Bernstein’s musical editor. Indeed, Bernstein’s last words to him were: “Take care of my music.”

The memoir is full of little vignettes and anecdotes, like the time he was called upon to sing at a party and instead recited a Yeats poem that as a student he had “struggled through five attempts to set” to music. (To hear my setting of it, please go to https://youtu.be/9Cl-D_rIfec.)

The memoir is full of little vignettes and anecdotes, like the time he was called upon to sing at a party and instead recited a Yeats poem that as a student he had “struggled through five attempts to set” to music. (To hear my setting of it, please go to https://youtu.be/9Cl-D_rIfec.)

There are lots of intriguing people referred to, frequently without names (is the “young composer who finagled his way into” a rehearsal Daron Hagen? (p.71) See my comment on him in my aforementioned NMC review article–scroll down to paragraphs 8 & 10: http://ljlehrman.artists-in-residence.com/PoliticalMusicalTheatre.html). (It has subsequently been learned that the “young composer” referred to by Charlie Harmon was not Daron Hagen, but someone else. Our apologies for any inaccurate implications that might have been inferred by the erroneous, speculative attribution – ed.).

A student oboist at Tanglewood, “a demure young girl,” is challenged by LB to play her 20-bar solo in Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony in one breath and does so “flawlessly,” at which point the cellos enter “messily” and are chided by the conductor: “You play like that after she just gave you that fantastic blow job?”

Unfortunately, there’s no index. To have provided one might have necessitated listing all the boyfriends of LB (as Bernstein liked to refer to himself, and be referred to). Harmon seems to have managed skillfully and tactfully to have escaped becoming one of them when, after three months on the job, “LB suddenly put his hand on my crotch,” apparently a fairly commonplace experience for all his assistants after that interval of time. Harmon “calmly took his hand away” and directed him to a shelf of pornography near his bed, saying “You’ll have a good time reading these.” What would I have done in a situation like that? (What would you?) Bernard Malamud’s strong negative reaction in 1964 had apparently poisoned LB’s avowed intention to complete Marc Blitzstein’s opera on Malamud’s story, which was why I eventually got to do it, with LB’s blessing. (See https://youtu.be/AvWK0UmA9u0.) Then again, being gay seems to have been a prerequisite, or at least an expectation, for anyone seeking to work for Bernstein – or on the staff at the Met, for that matter – a situation not lamented but rather celebrated, in certain circles, with performances of Bernstein’s setting of Whitman’s “To What You Said” and its reference to “these young men who travel with me.”

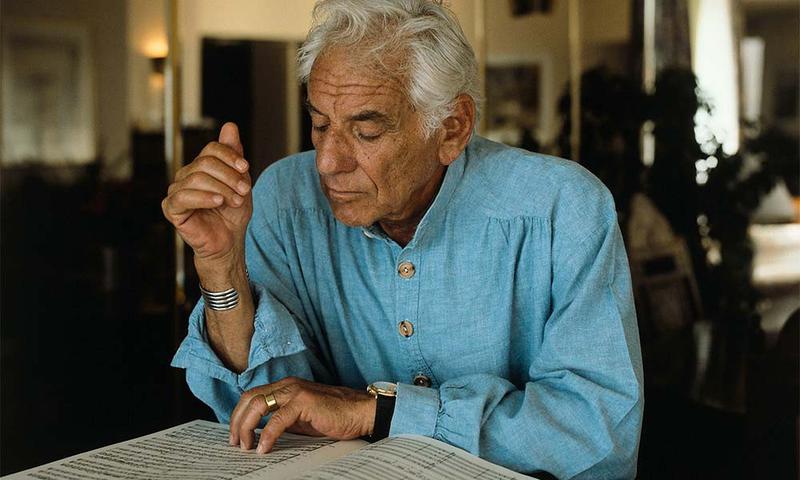

Nevertheless, the centrality of women in Bernstein’s life, his mother Jennie, his sister Shirley, his piano teacher and later secretary Helen Coates, his wife Felicia (at right), and to some extent his cook, Julia Vega (in whose memory the book is dedicated), is a theme in both this book and Bernstein’s elder daughter Jamie’s. It was Felicia who came up, in bed, with the wonderful rhyme for “Rovno Gubernya” sung by the Old Lady in Candide: “Me muero, me sale una hernia!” [I’m dying, I’m getting a hernia!”] A Chilean Catholic with a Jewish father, Felicia underwent conversion to Judaism the morning of her wedding to Bernstein. I remember arguing with my paternal grandmother, who was not happy, regarding my own first wedding: My bride had converted to Judaism only days earlier: “If it’s good enough for Leonard Bernstein, Grandma, it’s good enough for me!” Grandma gave in, and was one of the four chuppa (wedding canopy) holders. But in retrospect, maybe she was right. My first marriage lasted seven years, after which the bride eventually reverted to Presbyterianism. The Bernsteins’ marriage lasted longer, but ended with Felicia’s curse: “You’ll die alone, an old queen.” And toward the end of her life, she asked for a priest. Charlie’s book is full of supposed sightings of her as a ghost.

Nevertheless, the centrality of women in Bernstein’s life, his mother Jennie, his sister Shirley, his piano teacher and later secretary Helen Coates, his wife Felicia (at right), and to some extent his cook, Julia Vega (in whose memory the book is dedicated), is a theme in both this book and Bernstein’s elder daughter Jamie’s. It was Felicia who came up, in bed, with the wonderful rhyme for “Rovno Gubernya” sung by the Old Lady in Candide: “Me muero, me sale una hernia!” [I’m dying, I’m getting a hernia!”] A Chilean Catholic with a Jewish father, Felicia underwent conversion to Judaism the morning of her wedding to Bernstein. I remember arguing with my paternal grandmother, who was not happy, regarding my own first wedding: My bride had converted to Judaism only days earlier: “If it’s good enough for Leonard Bernstein, Grandma, it’s good enough for me!” Grandma gave in, and was one of the four chuppa (wedding canopy) holders. But in retrospect, maybe she was right. My first marriage lasted seven years, after which the bride eventually reverted to Presbyterianism. The Bernsteins’ marriage lasted longer, but ended with Felicia’s curse: “You’ll die alone, an old queen.” And toward the end of her life, she asked for a priest. Charlie’s book is full of supposed sightings of her as a ghost.

The last night I saw Bernstein, Oct. 25, 1984, backstage in West Berlin, he didn’t think he recognized me at first. But once he did, he jumped up and grabbed me, crying: “Where have you been?” Charlie’s notes for that evening appear in the book, on p.211, but don’t mention me. Then again, he barely mentions Michael Barrett, who became Bernstein’s assistant conductor after having convinced the maestro that he knew Blitzstein’s Cradle Will Rock very well, having conducted it from the piano with John Houseman’s company in the early 1980s. I had interviewed Houseman at Juilliard in 1970, after my 1969 Harvard production of it, but it would be another 10 years before the producer/director would express renewed interest in the piece. What if he had done so earlier? And what if I had been there?

In any case, many are the indebted to Charlie for what he has done, for Bernstein, his music, and Blitzstein’s too. Along with his numerous listed credits is the unlisted one of having engraved Volume 2 of the 3-volume Boosey & Hawkes Marc Blitzstein Songbook which I edited in 1999-2003. And he also helped us piece together an unpublished Bernstein setting of a text by Yoko Ono and her son Sean Ono Lennon, the story of which is told here:

https://youtu.be/x05FbpKN90E. Supplementing the book is a highly recommended interview with Charlie conducted by Mark Horowitz at the Library of Congress, posted here – http://www.loc.gov/today/cyberlc/feature_wdesc.php?rec=7934&loclr=eanw.

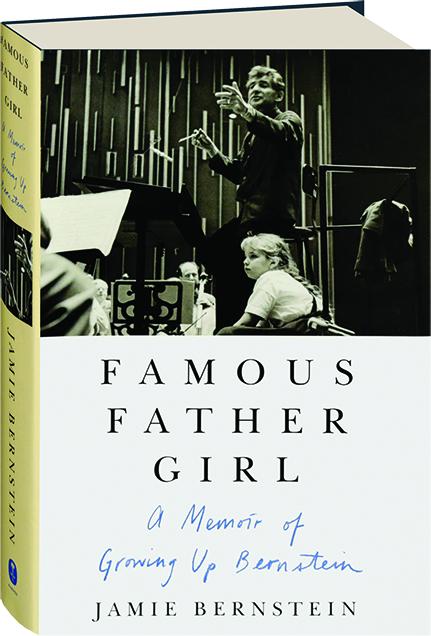

Bernstein By His (Elder) Daughter

I first met Jamie’s father at Harvard on Dec. 2, 1969, a few weeks after my Cradle production there – only Boston’s second, after his of 1939. (His reaction, on hearing about it, had been: “I’m glad somebody at Harvard still has taste!”) Almost exactly a year later, I had breakfast with Jamie at her Radcliffe dorm, in anticipation of both her parents’ coming to see my production of his Trouble in Tahiti and two Blitzstein Boston premieres at Lowell House, December 5, 1970. (December 2 seems to have been a rather fateful date, all told: Her marriage to another Harvard student, David Thomas, began December 2, 1984, but seems to have lasted only as long as the century. And last December 2, 2017, at CUNY’s Bernstein Marathon, I gave Jamie and her brother Alex the first news of a work by her father I’d just discovered, regarding which she emailed me: “Thank you, Leonard. What a find!” See http://www.soundwordsight.com/?p=2395. The previous time I had seen her and Alex, at a September 2014 book signing, she addressed her autograph to me as “the other Leonard”.)

Unlike the Harmon book, Jamie’s does have an index. But it’s a slightly weird one. Included are all the names of her major boyfriends (at one point she said she found herself sleeping with so many of them, asking herself not “Why?” but “Why not?”), but often without last names. And then there are others listed who are mentioned only by their first names in the text but given surnames in parentheses, as for example “Charlie (Harmon)”! Her brother Alex’s wife Elizabeth is mentioned, but her maiden name (Velazquez) appears only in the index. And her sister Nina’s husband Rudd is mentioned, but with no last name except in parentheses in the index (Simmons). Her own two children, Frankie (Francesca) and Evan, now have cousins Anya Micaela Bernstein, who appears in the index, and Anna Felicia (Simmons?), “a peach of a girl,” who does not!

Jamie’s book, like her life, is filled with anecdotes and self-wonderings. The morning I met her, she seemed intent on staying as far away from her father, and music, as she could, taking courses in English, Psychology, Writing, and really trying to find herself. Though Marc Blitzstein had been her godfather, and even written a piece honoring her birth – a short but lovely work which a number of people have played but I believe I was the first to record (and which will appear on my Blitzstein Solo Piano CD, issued by Toccata Classics in the coming months), she stayed away from performances of his music, and continues to do so – unless Barrett and his associate Steve Blier are involved.

Jamie’s book, like her life, is filled with anecdotes and self-wonderings. The morning I met her, she seemed intent on staying as far away from her father, and music, as she could, taking courses in English, Psychology, Writing, and really trying to find herself. Though Marc Blitzstein had been her godfather, and even written a piece honoring her birth – a short but lovely work which a number of people have played but I believe I was the first to record (and which will appear on my Blitzstein Solo Piano CD, issued by Toccata Classics in the coming months), she stayed away from performances of his music, and continues to do so – unless Barrett and his associate Steve Blier are involved.

A major focus of her book is her mother, and the grief she had to endure, from her father, but especially from the callousness of nasty writers, particularly Tom Wolfe. Jamie’s recent article on him for The Nation https://www.thenation.com/article/second-and-third-thoughts-on-tom-wolfe/ underscores that.

I remember feeling equally disgusted at the attention gathered by Wolfe’s “radical chic” put-down of the earnest efforts of liberals trying to right wrongs of the justice system, especially when the Harvard Crimson, which had printed a lovely preview

(https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1970/12/4/let-the-people-sing-out-pin/) and been expected to print a review of our Bernstein-Blitzstein evening instead printed a review (https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1970/12/10/hour-of-tom-wolfe-chic-er-than/) of Tom Wolfe’s book. (See my review of a recent opera based on another book by Wolfe, here: https://www.soundwordsight.com/?p=1659.)

But the wonderful anecdotes abound as well:

In kindergarten Jamie thought (as I did) that we were being taught to pray to “Guard.”

I’d read before about the home movie with Marc Blitzstein as the wicked Pharoah, and hope to be able to see it some time.

Her accounts of the gestation of Mass (which I remember began in December 1969, when Bernstein told all of us in the Dunster House Junior Common Room about his falling out with Franco Zeffirelli about a film about St. Francis – that eventually became Brother Sun, Sister Moon with a score by Donovan – “so now I have a whole room full of religious music, and I’m going up to the MacDowell Colony to figure out what the hell to do with it!”) are delightful, including the part about Nixon fearing the secret Latin message criticizing his government, which was of course: “Dona nobis pacem”!

A Norton Lectureship for Bernstein at Harvard was first proposed by my mentor Harry Levin that night of Dec. 5, 1970. But it took another two years to begin, develop and take place. Meanwhile Jamie, who had left New York for Cambridge, hoping to escape her father, found him practically right next door – where he, though not she, wanted him to be!

I never quite understood the relationship Mendy Weisgal (aka Michael Wager), in whose arms LB died, had with both LB and Felicia. Jamie goes a long way to explain it. A very warm individual, he was most receptive when I played him my completion of a Blitzstein aria for Sacco, quoting a phrase from Trouble in Tahiti, which he said he thought “Lenny” would have appreciated.

There is also a vivid description of Bernstein’s recording his own West Side Story, and the disastrous miscasting of Tony with the Spanish-accented Jose Carreras, when in fact Bernstein had wanted the English Wagnerian tenor Alberto Remedios, but couldn’t recall his name! That recording apparently set out to prove that this musical for Broadway singers could be sung just as beautifully, if not more so, by first-class opera singers, like Kiri Te Kanawa, Tatiana Troyanos, and so on, which is exactly what the new recording of The Cradle Will Rock seems intent on proving about that work. And while Chrisopher Burchett is not quite, or at least not yet, Howard da Silva, Jerry Orbach, or Alfred Drake (whom both Mauceri and I did not hear but wish we’d heard as Larry Foreman – though my parents did, in 1947!), the result is definitely positive, and worth building on. As the recent success of Regina in St. Louis shows, Blitzstein’s works deserve more and better productions, especially with orchestra.

Leonard Lehrman, whom Leonard Bernstein called “Marc Blitzstein’s dybbuk,” is the composer of 231 works to date, and also adapted and/or completed 20 of Blitzstein’s works (see http://ljlehrman.artists-in-residence.com/BlitzsteinCompletions.html). His award-winning work, “The Last Word,” written for the Alba Consort, will premiere at Hofstra this fall. He has been happily married to Helene Williams (who is Jewish, by the way) since July 14, 2002. His 12th opera, which he is writing for her, on Rosa Luxemburg, is scheduled for performances in NY and NJ next January. Visit his website at http://ljlehrman.artists-in-residence.com.

1 comment

Sorry, comments are closed.

[…] Review by Leonard Lehrman for soundwordsight.com […]